IFRS 9 in Practice: How Off-Market Terms Reshape Loan Valuation

Why does a standard loan restructuring suddenly create a gap between nominal balance and carrying amount — and what does IFRS 9 have to do with it?

Jakob Lavröd, Senior Quantitative Risk Analyst at Handelsbanken, walks through the practical logic of IFRS 9: from fair value and the rule of thumb “transaction price ≈ fair value,” to the role of the effective interest rate (EIR), the 10% modification threshold, and the alignment of cash flows for IRRBB/EVE — all to ensure that interest rate risk is cleanly separated from credit and commercial add-ons.

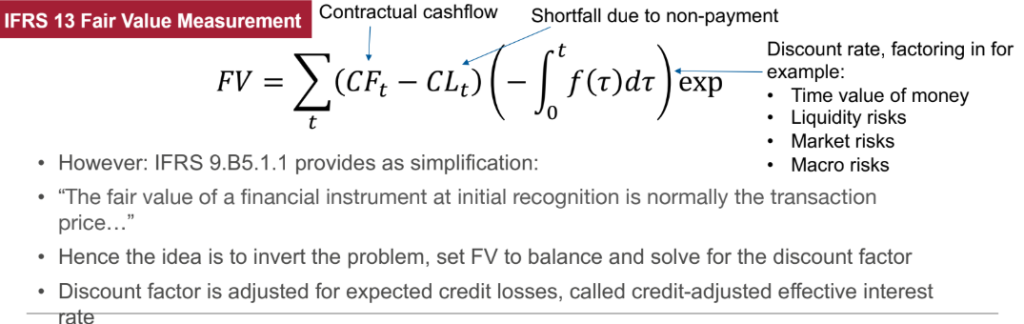

Fair Value: The Starting Point for Asset Measurement

IFRS 9 requires financial assets to be recognised at fair value on initial recognition. In essence, this is the present value of future cash flows. It starts with contractual cash flows, factor in potential shortfalls due to non-payment, and then discount those flows.

Importantly, the discount rate is not merely the time value of money. It may also embed liquidity premia, market risk, and macroeconomic risk components.

In the trading book, fair value is usually straightforward: there is a market, and therefore a price. In the banking book, things become less comfortable. Many loans have no liquid secondary market, meaning that a “market price” is not observable. In theory, this would require a full valuation model for every loan at origination.

This is where IFRS 9 introduces a critical simplification — without which the standard would be nearly impossible to apply to large loan portfolios.

Transaction Price as a Proxy for Fair Value

IFRS 9 allows a practical shortcut: in most cases, fair value at initial recognition can be assumed to equal the transaction price. In other words, the amount actually disbursed or paid is recognised at inception.

Without this assumption, banks would have to justify — loan by loan — the choice of discount rate, embedded risk premia, and their consistency with the observed transaction price.

However, this logic has limits. It breaks down when terms are off-market. Typical examples include:

- intragroup loans, such as lending to a subsidiary at 0%;

- distressed assets following substantial renegotiation;

- preferential products deliberately priced below market.

Off-market terms usually signal that the transaction contains an additional economic component beyond the loan itself — for example, a benefit or a form of remuneration. The easiest way to see this is through a concrete example.

Preferential Employee Loans: One Contract, Two Components

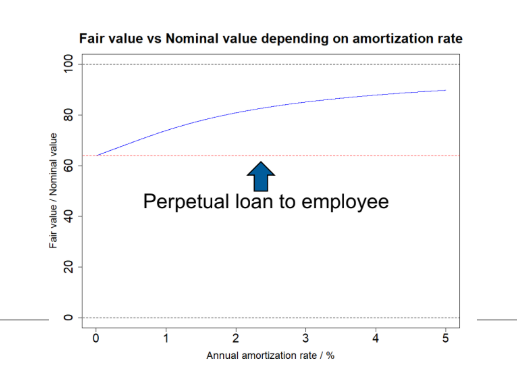

Consider an employee loan granted at a preferential rate. In our example, the employee rate is 2.25%, while the market rate for a comparable loan is 3.52%.

Looking only at the contract, the conclusion seems obvious: the loan is cheaper. From an accounting perspective, the spread between 2.25% and 3.52% represents an economic benefit granted to the employee.

Accordingly, the instrument should be considered in two parts:

- a loan at market terms;

- an employee benefit asset — the benefit related to staff remuneration, recognised evenly over time as additional compensation.

Under a simplified assumption — that principal is never repaid and only interest is paid — the fair value of such a loan would be around 63.5% of nominal. The reason is straightforward: interest paid at a preferential rate is discounted using the market rate.

If the principal is amortised, the picture changes. The preferential element exists for a shorter period because the loan balance declines over time. As a result, the gap between nominal and fair value narrows.

In short, when terms are off-market, IFRS 9 forces a separation between the “pure loan” component and any additional economic benefit. This separation directly affects the calculation of EIR, amortised cost, and ultimately the recognition of interest income.

This naturally leads to the next question: if a transaction embeds multiple components and risk premia, which rate should be used to recognise interest income and discount credit losses? Under IFRS 9, the answer revolves around the effective interest rate.

Amortised Cost: Why IFRS 9 Is Built Around EIR

How can accounting and risk be aligned in a bank where data and systems are typically segregated? An earlier conceptual approach — closer to fair value logic — would have required discounting all cash flows net of credit losses using a single fixed rate. But calculating a credit-adjusted EIR would require combining:

- contractual cash flows (usually in accounting systems)

- forecasts of credit losses (usually in risk systems).

In many banks, these data streams do not naturally converge. IFRS 9 therefore codified a solution that fits this operational reality:

- first, calculate EIR based solely on contractual cash flows — as if no losses existed;

- then, calculate expected credit losses (ECL) and discount them using the same EIR.

This results in a simple identity:

Amortised cost = gross carrying amount – ECL

One subtle but critical point follows. Riskier loans usually carry higher interest rates — rates that already compensate for credit risk. IFRS 9 then uses that same rate to discount ECL. This makes EIR the central parameter in the framework: it drives both interest income and the present value of credit losses.

Does EIR always remain unchanged? In most cases, yes. But there is an important exception — instruments with floating interest rates.

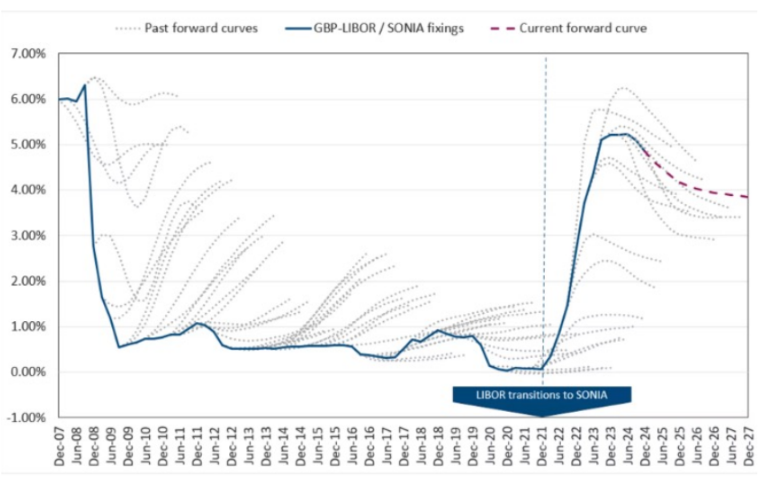

When EIR Changes: Floating Rates and Two Market Practices

IFRS 9 permits periodic re-estimation of future cash flows to reflect changes in market rates. When cash flows are updated in this way, EIR also changes. The rationale is to isolate pure interest rate risk, ensuring that movements in market rates do not distort credit loss measurement.

The practical question then becomes how to project future floating payments. Two approaches dominate in practice.

1) Forward-curve approach

Future cash flows are built using forward rates. This introduces market volatility into the calculations and requires yield curve integration into valuation engines.

2) Flat-forward approximation

The current floating rate is assumed to persist, and recalculations occur only when the rate actually resets.

An important caveat applies: if a product includes fixed fees (such as origination fees), EIR must be solved numerically — meaning the equation must be re-solved on a recurring basis. This quickly becomes a question of data quality and system architecture.

Floating rates are not the only reason cash flows change. Sometimes projections are revised because behavioural assumptions change — and IFRS 9 treats this case differently.

When Behaviour Changes, Not Rates

Assume behavioural assumptions are updated — for example, expected attrition or early repayment.

In such cases, IFRS 9 applies the following logic:

- EIR remains unchanged (the original rate at initial recognition);

- the gross carrying amount is recalculated as the present value of updated contractual cash flows, discounted using the original EIR;

- the difference is recognised immediately in P&L.

The effect can be material, yet it is often overlooked because IFRS 9 discussions tend to focus on staging and ECL. If not explicitly tracked, this impact can easily disappear into model calibration, reporting layers, or control processes.

A more severe scenario arises when contractual terms themselves are changed — triggering the well-known 10% test.

Modifications and the 10% Threshold

Consider a 15-year annuity loan with a 9% APR and a monthly payment of 1.01% of the outstanding balance. After one year, the borrower requests a rate reduction, which the bank approves. We compare “before” and “after” using present value discounted at the original EIR (9.38% in this example).

Scenario 1: Modification (<10%)

The rate is reduced to 8%, and the payment drops to 0.96%. In an annuity loan, PV falls proportionally to payments — to around 94.5%, a loss of 5.5%.

Accounting treatment:

- the instrument is not derecognised;

- the gross carrying amount is immediately reduced by 5.5% through P&L;

- EIR remains unchanged.

From a systems perspective, this means the gross carrying amount can fall below the nominal balance — and systems must be able to accommodate that.

Scenario 2: New Instrument (>10%)

The rate is reduced to 7%, payments drop to 0.90%, and PV falls to approximately 89.2% — a decline exceeding 10%.

In this case:

- the original loan is derecognised;

- a new loan is recognised, effectively refinancing the old one;

- if terms are commercial, the fair value of the new loan will be close to its carrying amount.

There is a critical risk implication. For SICR assessment, the “origination date” of the new loan is now today, meaning that the initial PD resets to the current PD.

A Special Case: Forbearance

If the rate reduction reflects the borrower’s financial distress (forbearance), the fair value of the new loan will be below carrying amount, reflecting both market rate changes and increased credit risk. If the asset is already in Stage 3, the new loan becomes POCI, and a different measurement logic applies.

Why EVE Can Be Overstated: It’s About Cash Flows, Not the Rate

IRRBB measures interest rate risk in the banking book — the sensitivity of loans, deposits, and other non-trading positions to changes in market rates. One of its core metrics is EVE (economic value of equity): the present value of assets minus liabilities under a given rate scenario.

In practice, EVE is often calculated by discounting future cash flows using a risk-free curve. But the key question is: which cash flows are being discounted?

If contractual cash flows are used mechanically, the result can be misleading. Loan rates typically include premia beyond pure interest rate risk.

In our example, an unsecured 15-year annuity loan with an 11% APR discounted at a risk-free rate produces a value of around 163 % to nominal. This signals an inconsistency (remember the transaction approximation from above, day 1 loan value should typically be 100 % of nominal, not 163 %), risk-free discounting applied to cash flows that already embed risk premia.

To resolve this, the discount rate is unbundled into two components:

f(t) = f₍risk-free₎(t) + cm(t)

where cm(t) is the commercial margin — all premia unrelated to pure interest rate risk.

Commercial margins are then transferred from the rate into the cash flows, producing transformed cash flows, from which:

- expected credit losses are removed; and

- all commercial margin components are stripped out.

Only then does EVE reflect what IRRBB is meant to capture: sensitivity to market rate movements — not a blend of interest, credit, and commercial effects.

Practical Takeaways

In practice, six checks are particularly useful:

- Where transaction price is equated to fair value — and how off-market cases are explicitly flagged.

- Whether systems distinguish nominal balance from gross carrying amount — especially after <10% modifications.

- How EIR is recalculated for floating-rate instruments (forward curves vs. flat-forward approximation) — and why.

- Whether P&L effects from changes in behavioural assumptions (e.g. attrition) are tracked separately.

- Whether the 10% threshold is clearly understood — modification vs. derecognition — and how it shifts the SICR baseline via PD.

- Whether IRRBB/EVE cash flows are consistent with risk-free discounting — i.e. stripped of credit losses and commercial margins.

Conclusion

IFRS 9 is often viewed primarily as an ECL standard. In reality, it starts with fair value, relies on the principle “transaction price ≈ fair value,” and builds amortised cost through the EIR → ECL linkage. Market rate changes are isolated (for floating-rate instruments), while other re-estimations flow through P&L. When moving to IRRBB/EVE, the same discipline applies: unless cash flows are properly transformed, the result will be a mix of risks — rather than a clean measure of interest rate exposure.

When the problem isn’t rates, but dates: where banks quietly lose money

Treasury. Interest rate risk (IRR). FTP. BP01. NII and NIM. Cost of Funds (CoF). Refixing risk (rate reset dates). P/L and Risk Limits. Swaps and shift fixings. Balance sheet management.