When the problem isn’t rates, but dates: where banks quietly lose money

What should a bank do when rates swing sharply — first soaring, then reversing — and even a small mistake in interest rate risk management can wipe out margin?

Marco Fischer, Head of ALM/Markets and a treasury practitioner with many years of hands-on experience, shares a systematic approach to managing interest rate risk. We explain why BP01 control alone is insufficient, how hedging decisions should be linked to Net Interest Income (NII) and Cost of Funds, and where refixing risk really sits in practice.

Treasury and the internal price of risk

Treasury is the function through which liquidity flows and key cash streams converge within a bank. It is also where the main market risks are concentrated — first and foremost interest rate risk, but also FX and liquidity risks. Crucially, this is where those risks ultimately translate into financial results: interest income and expense, margin, and overall P&L.

For this mechanism to be manageable, the bank needs a clear internal principle: how business units transfer risk to treasury and how that risk is priced internally. This is the role of FTP (Funds Transfer Pricing) — the internal transfer price.

From a treasury perspective, FTP defines the price at which treasury assumes interest rate risk and liquidity from the client-facing business.

We build FTP based on matched maturities: the internal price is linked to a market benchmark of the same tenor and fixed at deal inception for the full life of the transaction. In practice, this means if the business grants a client a five-year fixed-rate loan, we take a market price of comparable maturity — for example, a five-year swap rate and liquidity costs for term matched funding — and use it to construct the internal price.

For the business, this is critical: margin becomes transparent, comparable, and fixable. It can be managed at the product level.

And here lies the fundamental nuance. Fixing margin at the business-unit level via FTP does not mean that margin is automatically protected at the bank-wide level. From this point on, responsibility shifts to the Treasury. The Treasury must manage the bank’s overall interest rate position — and do so in a way that hedging and risk management decisions do not destroy margin at the balance-sheet level.

All this leads to the question: how exactly do we measure interest rate risk, and what do we manage on a day-to-day basis?

In many banks, the first answer is BP01.

Why BP01 alone is not enough

In practice, interest rate risk is often managed through BP01 — the sensitivity of a position’s value to a one-basis-point (0.01%) move in interest rates. Simply put, BP01 answers the question: how much does the value of a position change if the yield curve shifts slightly?

BP01 is a genuinely useful metric. It disciplines the risk position, highlights maturity gaps (where risk is excessive or insufficient), supports limit setting, and helps determine where and how to hedge — for example, via swaps.

However, BP01 has a built-in limitation: it measures value risk, not income risk. If a bank manages only this metric, it can end up with a tidy sensitivity profile while simultaneously damaging the very thing the balance sheet exists for — interest income and margin.

This is why focusing solely on BP01 leaves us effectively blind in one eye. We lose sight of the average coupon embedded in each risk bucket.

Why does this matter? Imagine a position with an average coupon of 3%, while the market is already at 4%. Aggressive hedging may effectively give away 1%. When the average banking margin is around 1.5–1.6%, that single decision can consume most of the result.

The conclusion is straightforward: one lens is not enough. BP01 is necessary — but it must be complemented by a second “eye” that keeps us anchored to interest income.

The second eye: NII, NIM, and Cost of Funds

If BP01 answers the question “what happens to portfolio value when rates move,” the second perspective answers “what happens to the bank’s interest result.”

This view relies on several core metrics:

- NII (Net Interest Income) — interest income minus interest expense

- NIM (Net Interest Margin) — NII scaled to the size of the balance sheet, enabling comparison across periods and institutions

- CoF (Cost of Funds) — the average rate at which the bank funds itself

- Annualization — expressing metrics on an annual basis to eliminate seasonality effects

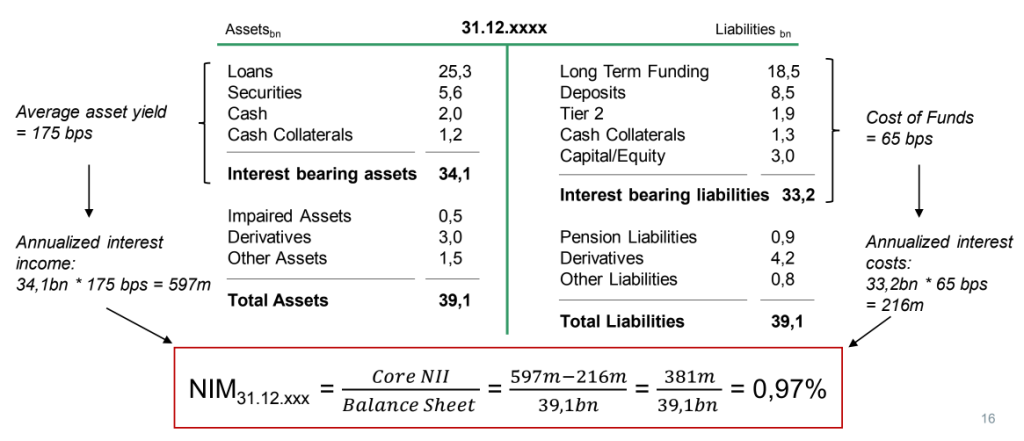

A simple numerical illustration makes this tangible. If the average yield on assets is 175 bps (1.75%) and the cost of funding is 65 bps (0.65%), annualized calculations produce an indicative margin; in this example, NIM is approximately 0.97%.

Step by step:

- Interest-earning assets of 34.1bn × 1.75% ≈ 597m annual interest income

- Interest-bearing liabilities of 33.2bn × 0.65% ≈ 216m annual interest expense

- NII ≈ 381m

- NIM ≈ 381m / 39.1bn ≈ 0.97%

It is important to remember the limitations of this approach. These calculations often assume a constant balance sheet — as if the balance does not change throughout the year. In reality, it always does. Incorporating planned balance dynamics is possible, but requires a more complex data and modelling setup.

So why keep this perspective anyway? Because interest income is the core driver of bank P&L. BP01 manages sensitivity, but only NII and CoF reveal whether hedging decisions are undermining the economics of the bank.

This leads to a practical rule: before executing swaps, one must understand not only the BP01 impact, but also the average coupon within the bucket or gap — and how the transaction changes the economics. And it is precisely here that a frequently overlooked risk emerges — because it is not only about tenors, but also about the calendar.

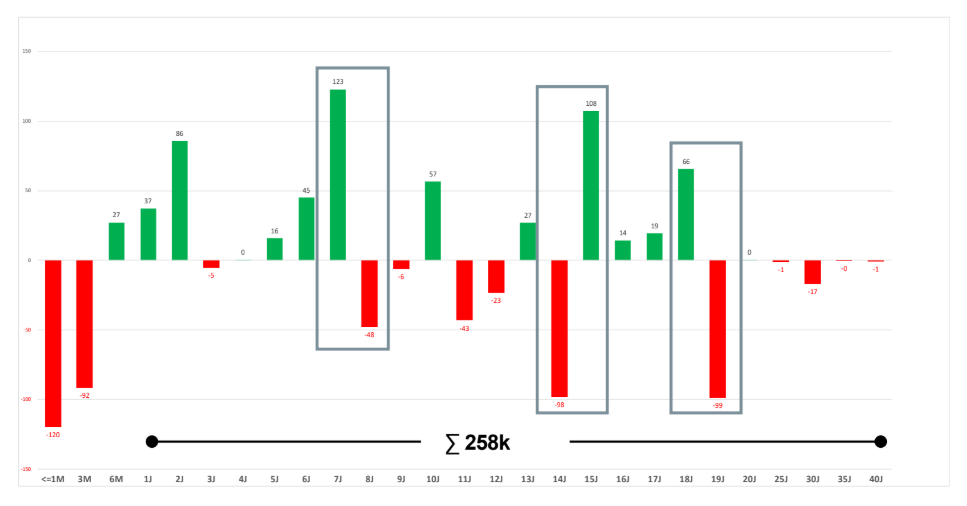

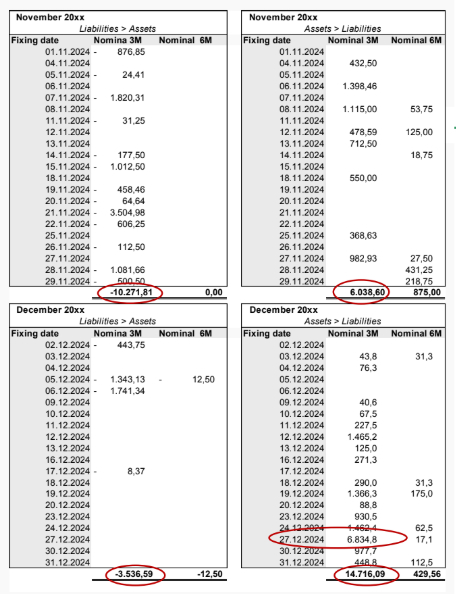

Where risk hides: reset dates and the quarterly bias

Refixing risk arises from mismatches between rate reset dates on assets and liabilities. On paper, maturities may look similar, but in reality rates are repriced on different days — and this timing mismatch creates volatility.

A typical pattern looks like this: on the asset side (lending), rate resets tend to cluster toward quarter-end, while on the liability side they are spread more evenly throughout the year. Managing this “head-on” is almost impossible. Clients will not align their behaviour with the bank’s risk management logic.

The real lever therefore sits inside treasury: synchronising the funding desk and hedge roll dates with the structure of the asset side.

Refixing risk often grows not because someone miscalculates, but because functions operate in silos. When asset and liability calendars are not reconciled into a single picture, risk accumulates between units — until it starts hitting results and limits.

How to measure this risk — and what happens if you miss it

To manage this, we translate the “calendar problem” into numbers via a stress scenario with a 200 bps curve shift. The risk profile depends on where we are within the quarter: it increases as the reset date approaches and collapses immediately after the reset.

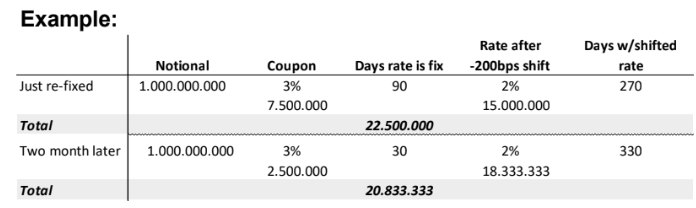

A simplified example:

Take a notional of 1bn with a quarterly coupon of 3%. Immediately after reset, the rate is fixed for 90 days, leaving a “risk period” of 270 days. Under a −200 bps scenario, the rate drops to 2%, producing a result of 22.5m.

Two months later, the fixed portion is only 30 days, the risk period expands to 330 days, and the result becomes 20.83m.

The message is simple: even with identical tenors, the risk profile depends on the calendar. If not kept within limits, this risk quickly translates into breaches.

The practical solution is shift fixings — harmonising asset and liability reset dates by moving critical repricings out of “bad” months using a set of swaps with different roll dates.

This approach comes with trade-offs:

- Pros: fast to implement, relatively inexpensive

- Cons: usually requires a large derivatives volume, affecting other KPIs (such as balance sheet size)

The takeaway is clear: refixing risk is best captured early. Once limits are breached, solutions still exist — but the cost of rapid correction is almost always high.

What it takes to manage risk systematically

The first step is basic “housekeeping” — fundamental controllability. Avoid focusing on a single pocket of risk or overcomplicating matters prematurely. Start by reviewing exposures and checking whether they actually offset each other. In many cases, part of the risk is naturally hedged within the balance sheet — and only the residual should be taken to the market.

From there, the logic usually unfolds in stages:

- Net positions internally

Align assets and liabilities across comparable maturities to avoid hedging what is already naturally covered. - Model non-maturity deposits correctly

For NMDs, use a replication portfolio approach: part behaves like overnight funding (more volatile), part like a longer, stable component. Deposit beta — the degree of pass-through from market rates to client rates — is critical here. - Capture non-obvious positions

Non-interest-paying equity or pension liabilities can be translated into risk metrics via offsetting positions (e.g., BP01 equivalents) to reflect the full risk profile. - External hedge last

Only when residual risk is clearly understood should external hedging be executed — and only to the minimum extent required.

For this logic to work, a solid system backbone is essential:

- IT architecture: a front-office system for trades and an independent risk-control system capable of simulations and risk views independent of trading

- Data: notionals, BP01, average coupon, rate type (fixed/floating), tenor, IFRS category, annualized NII/NIM, and stress-testing capabilities

- Governance: risk appetite, limits, policies, and clear role separation between treasury and ALCO

This basic toolkit is often missing — and without it, interest rate risk management becomes reactive rather than systemic.

Conclusion

Taken together, this is not a “hedging recipe,” but a management framework.

It starts with transparent internal risk transfer via FTP — without it, business units and treasury operate under different economic logics. It then acknowledges the limitations of BP01: without average coupon and NII/CoF perspectives, sensitivity can be improved at the expense of margin. Finally, it keeps the calendar dimension in focus — refixing dates can quietly accumulate risk and force action only once P/L- or risk limits are breached.

In the end, what matters most is not individual instruments, but the order of thinking: first transparency and basic controllability, then two complementary perspectives (value and income), and only then — the market and derivatives, in the minimum volume necessary.

Islamic Banking in Treasury: A Practical Case from Kazakhstan

Islamic banking in treasury: how to operate without interest while still using a full toolkit for client financing, liquidity management, investment portfolios, and foreign-exchange risk. Using the example of a Kazakhstani Islamic bank, we examine real products—from Murabaha and Ijara to Sukuk and Wakalah/Mudarabah investment deposits.

IFRS 9 in Practice: How Off-Market Terms Reshape Loan Valuation

How fair value, the effective interest rate (EIR), and expected credit losses (ECL) interact under IFRS 9; why off-market transactions must be unbundled into fair-value compon